Though we increasingly understand what happens online is not any less ‘real’ than what happens offline, it can be easy for some to perceive that they are talking to a computer when they post on social media, rather than publishing within a space of public social communication. For example, there have been many cases on Twitter and Facebook where disgruntled employees post inappropriate messages about their bosses, which they would not have uttered offline. The logic here is that the act of typing on a keyboard can sometimes lead to a perception that what you type is somehow less ‘real’ or perhaps kind of trivial.

But, of course, it is no less real or trivial. Social media sites such as Twitter have been host to racialized talk about immigration or can respond to events in racialized ways (for example Charlene White’s refusal to wear a poppy). In terms of anti-racism, Twitter users often police the medium for ‘casual’ forms of racism. It is the latter that I have taken a particular interest in within my research of social media and Twitter specifically. So when Madonna used the N-word on January 17, 2014 via Instagram, my casual racist sensor went off. For those not familiar with this incident, Madonna Instagrammed a picture of her son Rocco Ritchie while boxing, adding the caption: “No one messes with Dirty Soap! Mama said knock you out! #disni**a”. Madonna’s million plus Instagram followers received the image, which nearly instantaneously circulated to Twitter and its diverse audiences. Not only is the use of the N-word clearly inappropriate, but embedding it within a racial hashtag contributes to larger hashtag-based casual racist discourses on Twitter and other social media. Madonna’s Instagram photo caption reveals that she sees a certain normalcy of the N-word. More dangerously, her worldwide celebrity status, legitimizes racial hashtags through her casual use of the N-word on Instagram.

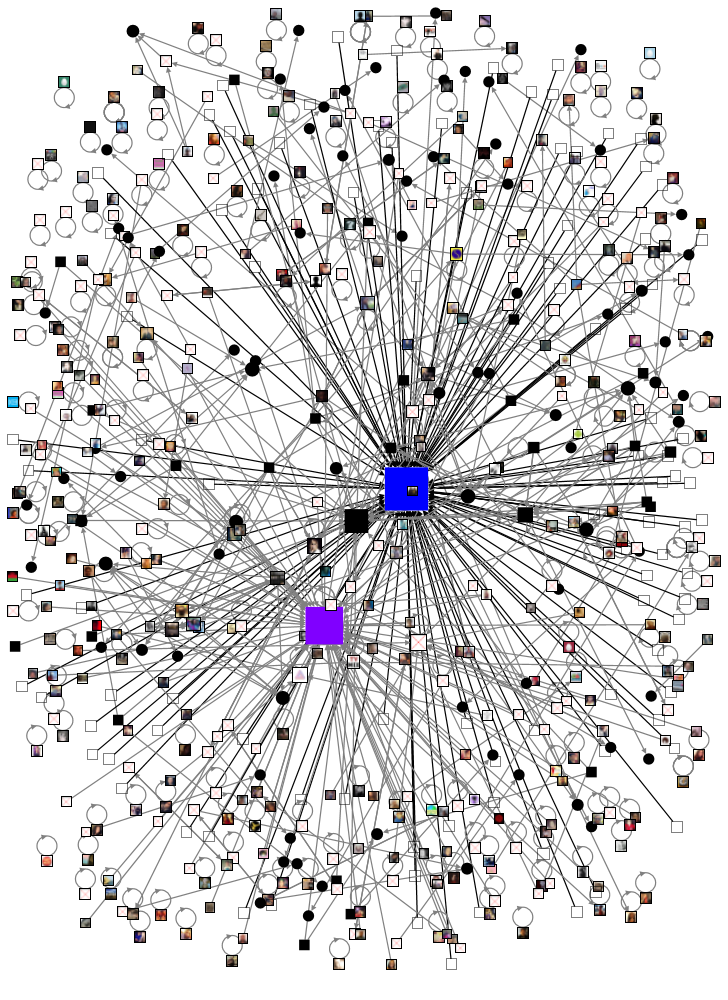

Though it is important to make larger arguments about how the Madonna incident is a case of casual racism which has major implications, I think it is also important to understand the micro-level interactions on social media which Madonna prompted. To do this, I first collected all tweets with the #disni**a hashtag and then did the same for all tweets containing ‘Madonna’. The latter had very little to add in terms of data that was not already encompassed by the former. As #disni**a was a more inclusive search term, I created a graph of this network.

[squares represent users with more than 1,000 followers and the size of the user icons is scaled by the number of RTs or @mentions].

The noticeable black square (between the blue and purple squares) represents Madonna (rather than her tweeting out, people are tweeting at her). The blue square represents an East Asian-American actor/comedian on MTV (@Traphik ; 420,000 followers) who tweeted “Lol Madonna hashtagged a pic with #disnigga!? Do u kids see what uve done! It’s like grandpa saying “yo homie G” cuz it’s all he hears!”. The purple square represents a black female blogger (@luvvie) with over 27,000 followers who had two tweets heavily retweeted, “Madonna talmbout she called her son #DisNigga as term of endearment. I wanna lock her in a stadium of seats so she can pick plenty to have” and “If Madonna is calling her white son #DisNigga, what is she calling her little Malawian son? I’m unable to deal.” It is interesting that the two centers of the tweet network for #disni**a are not white and both use humor to interrogate Madonna’s Instagram incident. From a social graph perspective, they steered the conversation on Twitter.

Madonna’s racist outburst was clearly racist and was covered in the popular press as such. The ‘thought leaders’ on Twitter around the #disni**a hashtag, however, saw this as an opportunity to both ridicule Madonna (e.g. PTraphik labeling Madonna as an out of touch Grandma), but also reflect on her use of the racial slur. Madonna made clear that she did not intend the comment as ‘a racial slur’ and that she is ‘not a racist’. However, this incident highlights the extreme prevalence of racialized language on social media, when even a self-purported liberal celebrity who pushed gender boundaries in the 80s/90s uses a racialized hashtag. I think this incident makes clear that we should not be lulled into a false sense of security of de-racialized virtual spaces, but that the virtual can also give us glimpses into peoples’ backstage lives, which we would not usually have access to offline. Ultimately, the Material Girl has been shamed on Twitter. It would have been nice to see more of a critical engaged discourse on Twitter about the incident, but that is not how social media usually operates.

A version of this blog has been published by The Runnymede Trust on their Race Card blog.